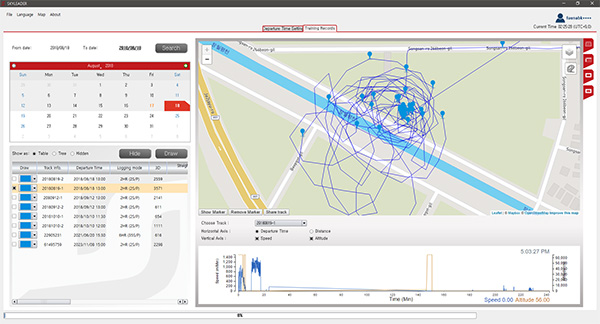

1. Homing Ability of Racing Pigeons Observed Through Personal Experience

In the mid-1980s, I had the experience of raising about 20 racing pigeons in a small loft I built on the veranda of an apartment in Yeouido, Seoul. The training method was simple but systematic. With a friend who lived in Ansan — about 25 kilometers away — I transported the pigeons by car each evening, and my friend released them one by one the following morning.

Among them, one pigeon stood out in particular — known as "BF." This bird consistently returned to the loft in Yeouido in about 15 minutes. Other pigeons typically arrived between 25 to 45 minutes later. Although their performance improved with repeated training, none matched BF’s speed and accuracy. After about ten individual training sessions, I began releasing the group all at once — and surprisingly, the entire flock returned in roughly 15 minutes, suggesting that BF was likely acting as the leader and guiding the group home.

One key detail to note is that the pigeons trained together were of a similar age — all relatively young birds. While recent research suggests that older, more experienced pigeons have greater influence in determining routes, in this experiment, even without notable differences in experience, a particular individual (BF) emerged as a leader. This is an intriguing deviation from the common assumptions of leadership hierarchy in pigeon flocks.

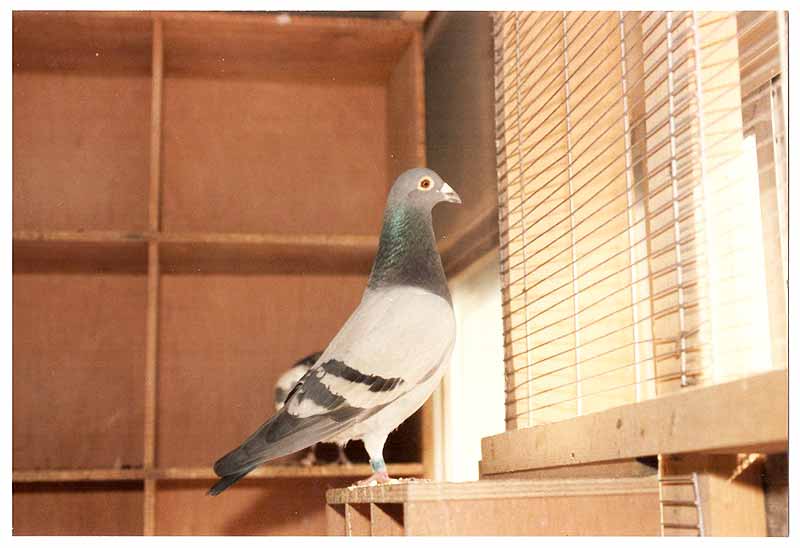

Kor 85-2145 BB "Blue Fantasia"

BF & Dordin hen

Kor 81-3236 BW "Duke"

Duke is the sire of BF.

2. Homing Ability and Group Navigation in Recent Scientific Research This personal experience interestingly intersects with modern scientific findings. Below are some relevant studies and their key points: [1] Familiar route loyalty implies visual pilotage in the homing pigeon (PNAS, 2004)Using GPS tracking to analyze repeated flights of homing pigeons, this study found that pigeons tend to adhere to familiar routes, even when they are not the most efficient. This suggests that pigeons use learned visual landmarks — known as “visual pilotage” — to navigate. [2] Route-dependent switch between hierarchical and egalitarian strategies in pigeon flocks (Scientific Reports, 2014)This study revealed that pigeon flocks dynamically switch between hierarchical (fixed-leader) and egalitarian (shared-decision) strategies depending on the route and conditions. This directly relates to the possibility that BF acted as a leader in a specific situation — much like the study’s description of context-based leadership. [3] Magnetic fields and orientation in homing pigeons: experiments of the late W. T. Keeton (PNAS, 1988)This classic experiment tested the impact of magnetic interference by attaching magnets to pigeons under overcast conditions. While the magnetic field sometimes disrupted navigation, in many cases it had little effect — suggesting that magnetism is just one of several factors in homing ability. [4] Interaction rules underlying group decisions in homing pigeons (Royal Society, 2013)This study analyzed how pigeons interact during group navigation. Rather than following a single dominant leader, the flock’s direction was determined through real-time negotiation and mutual interactions. However, it was also found that individuals with higher navigational accuracy or experience exerted greater influence — supporting the idea of “competence-based influence.”

3. Where Experience Meets Science: A Concluding Thought The consistent and accurate return of BF and the flock’s rapid return during group release strongly suggest that BF played a leadership role. This personal observation aligns well with scientific theories — especially the hybrid models of flexible leadership and interaction-based decision-making. Research increasingly emphasizes dynamic leadership and influence based on individual competence, rather than fixed hierarchies. In real-life training situations, skilled individuals like BF can take on critical roles even without formal dominance. In short, BF was a “leader” in the practical sense and a “key influencer” in the scientific framework. This case shows how personal experience and scientific inquiry can enrich one another — forming a mutually reinforcing perspective on animal behavior.

|